Journal and Courier, Lafayette, Indiana, Monday, February 21, 1966, page 2

By PETER ARNETT, SAIGON, South Viet Nam (Associated Press) - A young infantryman named Stephen Laier has shown in 15 pain-filled days that in some men the only

limit to courage is death.

The courage of Laier, 18 years old, 6 feet tall and 225 pounds, almost defies comprehension by men who have never been wounded in

battle.

From the moment he lost both his legs to a bursting Viet Cong mine early in February, to the time 15 days later when life finally ebbed from his body,

Laier fought for survival with a tenacity that brought tears to the eyes of those who knew that his wounds were mortal. The doctors did everything to save him.

Big, blond Laier, from Fort Wayne, Ind. - 2526 Clara Ave. - had shown he was a man well worth saving.

He suffered his terrible wounds Feb. 4 as an ambush patrol from his company from the 1st Battalion, 16th Regiment, 1st Infantry Division, chased a sniper and

got hit with hidden mines wired to detonate simultaneously.

Three of the men were killed instantly, the remaining 11 wounded. Laier, close by the mines when they burst, lost his legs in what doctors term "a traumatic

amputation."

With wounds this terrible, most men slip into shock and die.

Laier, the radioman for the patrol, was made of sterner stuff. He told doctors later he knew he was the only man alive capable of operating his radio equipment.

He tied rough tourniquets around the stumps of his legs and groped for his radio in the undergrowth under some wild rubber trees. The blast had upset the

calibration of his radio.

In the gathering dusk, Laier returned the set, a difficult job for a whole man. Then he began calling to his company headquarters at

nearby Lai Khe to notify them of the catastrophe that had befallen the squad.

Laier then attempted to call down medical helicopters but they could not land because of the darkness. A patrol from his company arrived on foot, guided by Laier.

By this time, 35 minutes had gone by.

His company commander Capt. Edward Yaugo, from Warren, Ohio, asked Laier, "Is there anything we can do for you?"

Laier replied, "Yes, you can get me some morphine."

The fight for Laier's life was on.

Dr. Kris Keggi, from El Paso, remembers Laier being brought into the 3rd Surgical Hospital at Bien Hoa that night.

"Medically, he was dead then," Keggi said. "We probed his veins. There was no blood in them. He was literally down to his last drop of blood."

Keggi and his aides pumped six pints of blood into the youth and he came around.

Fifteen days later a total of 60 pints of blood had been given him, literally replacing his normal blood supply six times.

Most men die after transfusions of 20 pints of blood. Too many complications set in. But after 30 pints, doctors thought Laier might have a chance.

"His will to live was tremendous," Dr. Keggi said.

Laier eventually developed a multiplicity of complications, requiring further operations on his legs.

NO COMPLAINTS

"We fought against amputating his legs at the hips," Keggi said. "We hated to do that. This man had been a football player, and he told us that he wanted to get out,

wear tin legs, and walk again."

At no time did Laier complain about his misfortune.

"Maybe it was because his grandfather had lost his legs because of diabetes. He didn't seem afraid to face life," said Capt. Marguerite Giroux, from Malone, N.Y.,

the operating room nurse.

Nurse Giroux helped Laier write letters home to his mother and his girl friend.

"He was so brave that he didn't even want to tell his girl friend that he was so sick. He said she should not have to worry about him," nurse Giroux said.

To help sustain him in his quiet, desperate fight for life, Laier, a Roman Catholic, asked for a priest. As many as five Catholic chaplains at a time came

to visit him. Nurse Giroux said he prayed constantly.

A FUNSTER

Medical Spec. Jose Mares, from Albuquerque, N.M., remembers Laier as a funster.

"He kept telling us he really wanted to be a barber, not a soldier. Then he said he wanted to sit by a lake and fish his life away," Mares said.

With this kind of spirit, Laier raised hopes of the doctors that somehow he would pull through. But as the extent of his medical complications became apparent,

this hope began to fade.

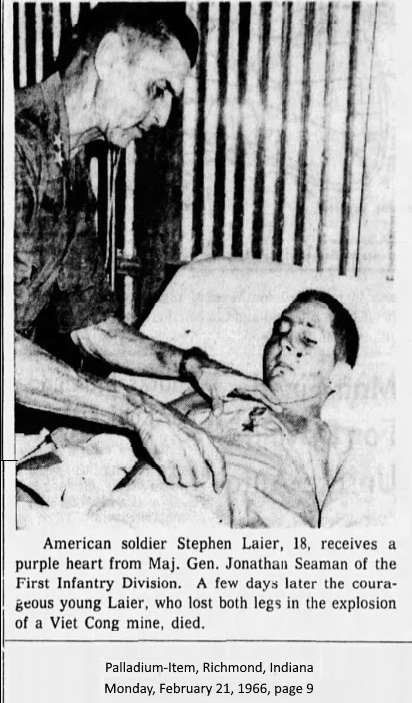

Laier's commanding officer, Major General Jonathan Seaman, visited Laier several times. Seaman was so impressed with the young radioman that he wrote a friend,

"This is one of the bravest men I have seen in 30 years as a soldier."

Seaman presented Laier a Bronze Star with "V" for valor [upgraded upon his death to Distinguished Service Cross], and told him; This is the highest award in my power to present you. I wish I could present you with a

higher one.

Laier told his commanding general; "I want to stay in the Army when I get my new legs."

Laier's spirit never faltered. It was his body that failed him.

In an epitaph to the young radioman, Gen. Seaman said. "With men like Laier, our division, our Army, our country will always be great." Death did not come

as a merciful blessing for the terribly wounded infantryman. He tried hard not to die.